Inside the Pack: Examining Rally Rd.’s Platform of Baseball Card Investing

Back in July, a startup investment site called Rally Rd. made waves in the card collecting community. Typically a platform for purchasing shares of expensive cars, Rally Rd. announced they’d be branching out into baseball cards, offering fractional shares of a T206 Honus Wagner card to the masses starting in August. That month came and went with no news, and the Wagner disappeared from its app, despite still appearing on its website as “Coming Soon.” (For what it’s worth, I emailed the site at the beginning of September about this, and was told by a representative from the Member Success team, “We are waiting on a few i’s and t’s to be dotted and crossed – we should have more news on this within the week!” That was over two months ago, with no further news.)

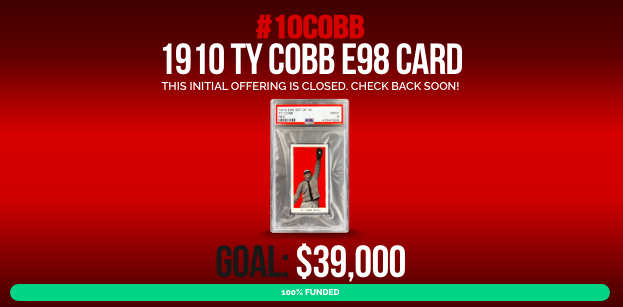

But in the meantime, they have branched out into baseball cards with a few other iconic cards. The first offering from Rally Rd. was a 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle graded SGC 7. The site offered just 1,000 shares at $132 each. Last week, the second card was offered — a 1910 E98 Ty Cobb card graded PSA 9. This time, the site offered the 1,000 shares at $39 each. In both instances, the shares sold out in minutes. The sales have earned Rally Rd. plaudits for redefining what investment means for a new generation and democratizing collecting to allow people to invest in something they’d otherwise never obtain on their own.

I do love the idea of being able to see I own a fraction of a card I would never otherwise be able to own. However, I have some concerns with this model, as it seems to be designed more for investors who are looking for something trendy to invest in than actual card collectors.

The primary issue I have with the model is that it is difficult to monetize your investment. Rally Rd. draws comparisons to the stock market, but it really isn’t similar for a number of reasons, namely:

- The stock market is open every non-holiday weekday. You can trade your shares at any time you choose. This isn’t the case with Rally Rd., where trading doesn’t open for 30 to 90 days after an asset’s initial public offering. After that, there is a monthly trading window in which you can buy and sell shares; that window is then closed again for 30 to 60 days until the next trading window.

- Stock exchanges have many many investors; Rally Rd., on the other hand, is a much smaller community. For example, the 1,000 shares of the Ty Cobb card went to just 193 investors, and the 1,000 Mickey Mantle shares were split among just 264 investors. This means that not only do you have more opportunity to sell your shares of a stock as opposed to a Rally Rd. asset, but you have a much, much wider audience of folks to sell to. If you want to sell shares of a stock at a fair market price, you will find a buyer pretty quickly; on Rally Rd., you may struggle simply because the pool of investors is much smaller.

- Shares of stock grant you certain allowances that shares of an asset do not. Buying a share of stock gives you fractional ownership of the company, and as such, many companies offer you the ability to vote on decisions either in person or by proxy. Many companies pay dividends to investors who own its stock. But of course, the big difference is that companies are actually producing something of value — a profit — that would cause others to want to take part in its ownership. Companies file regular financial disclosures to alert investors to the monetary status of the corporation; a Mickey Mantle card is going to sit at the Rally Rd. headquarters indefinitely. The value may go up if similar cards sell for more on the open market, but it is a piece of cardboard with no intrinsic value, as opposed to a company, which, even when losing money, still owns real estate, office equipment, and other liquid assets that could be converted to cash if need be.

And that’s really the biggest cause for concern I have with the platform. As a part-owner in a Mickey Mantle or a Ty Cobb or, maybe one day, a Honus Wagner, you own a hypothetical piece of cardboard. The only way to make money on your investment is to hope that once every few months, when trading opens, someone values the card at slightly more money than it was valued for when you bought it. Yes, it’s true that the same is the case for stocks — that the only way to make money (other than dividends) is to sell the stock to someone else for more than you paid for it. However, there are reasons a stock would increase in value drastically in a short period of time: good earnings, a breakthrough product, a new drug trial, a good acquisition, and so on.

A baseball card, however, is not doing anything to increase in price enough to justify the investment. The only way it goes up in value is if its perceived value gets higher. And because Rally Rd. is never actually selling the card, the only way for the perceived value to get higher is for other similar cards to sell for more money. Therein lies the rub: high end, high grade vintage cards like these don’t come up for sale often, so knowing what their value is on the open market is difficult. (One could argue that it would be easier to determine a value, and therefore easier to increase the valuation, of a 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle PSA 1 than it is an SGC 7 of the same card.

The problem can be illustrated fairly easily with the Mickey Mantle card, with 1,000 shares sold at $132 each. Let’s say that we actually accept the valuation of the card at $132,000 (which, it should be noted, is fairly high, as was the $39,000 valuation of the E98 Ty Cobb). Now let’s assume that, for no reason other than inflation and an increase in scarcity due to collectors hoarding them, values of 1952 Mantle cards increase by 20% across the board over 5 years. That kind of jump is almost unheard of for a baseball card in such a short time, and a 20% return on investment is very nice in general. For all your patience over those 5 years, your $132 investment would have increased to…$158. If you invested big on the Mantle’s IPO day and bought 10 shares, or 1% of the outstanding shares, you would have laid out $1,320 over 5 years to make a profit of just $264. The problem here is that in addition to the asset not acting like a stock, and not doing anything to generate a huge bump in value, there simply aren’t enough shares outstanding to result in a big payday. While buying hundreds and thousands of shares of a stock is commonplace, it’s impossible with this platform, primarily because if you had the money to do so, you could just buy the card (or a similar card) itself, but also because there are fewer shares outstanding. You will likely never find enough sellers to become an owner of enough shares to make a large return.

Ultimately, I’d personally prefer taking the money I would otherwise invest in a card I would never get to have possession of and an asset I would have difficulty monetizing and instead purchase a card meaningful to me that I can get enjoyment out of while it (hopefully) gains value over the years. The ability to tell people that you own a part of an iconic card is a really neat angle, though, and it’s certainly one I can understand the allure of. It’s a decision each collector — or investor — will have to make on an individual basis.