Inside the Pack: What Makes Something a Baseball Card?

What do you consider a baseball card? Is a sticker a card? What about a coin? These questions have come up fairly frequently among myself and other collectors. I know where I stand, and there are plenty of people who have the same opinion as I do, and many who think I’m crazy. I won’t reveal my position just yet. Instead, I want to take a logical journey through the concept of baseball cards.

Let’s start with the most specific definition we know we all can agree on. A baseball card:

(1) Is a 2.5” by 3.5” rectangle

(2) Contains an image of a baseball player on the front

(3) Contains statistics and/or biographical information on the back

(4) Is printed on paper, cardboard, or a similar material

(5) Is distributed in a pack

(6) Was created with the intention of being collected

These attributes create the most specific description of a baseball card that absolutely everyone can agree upon. One by one, we can begin to expand these attributes to include more items under the banner of “baseball cards.”

We’ll start with attribute (1) — that baseball cards are a 2.5” by 3.5” rectangle. This one is easy to knock off our list, because prior to 1957, cards were never this size. Bowman cards were smaller, Topps cards were larger, and tobacco cards were minuscule compared to today’s measurement. So, we know that measuring 2.5” by 3.5” is not a requirement for calling something a baseball card.

I think we can also ditch the rectangle idea fairly easily as well. Vintage issues like 1969 Topps Deckle Edge have edges that aren’t straight. Some sets, like 1947 Bond Bread and 1953/54 Stahl-Meyer, have rounded corners. Other newer sets, like 2003 Fleer Hardball, were circular in design. These would all otherwise be classified as baseball cards, and their non-rectangular shape would be no reason to exclude them from the category. So, size and shape are no longer qualifying attributes.

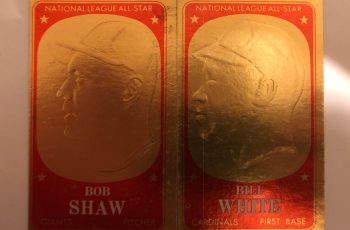

Let’s skip to attribute (3), because that’s the easiest one to knock off our list. Tobacco cards, like T206, had advertisements on the back. 1951 Topps Red Backs had a red baseball diamond and that’s it (hence the set name!). Some relic cards contain nothing but a legal statement or a congratulations on the back.

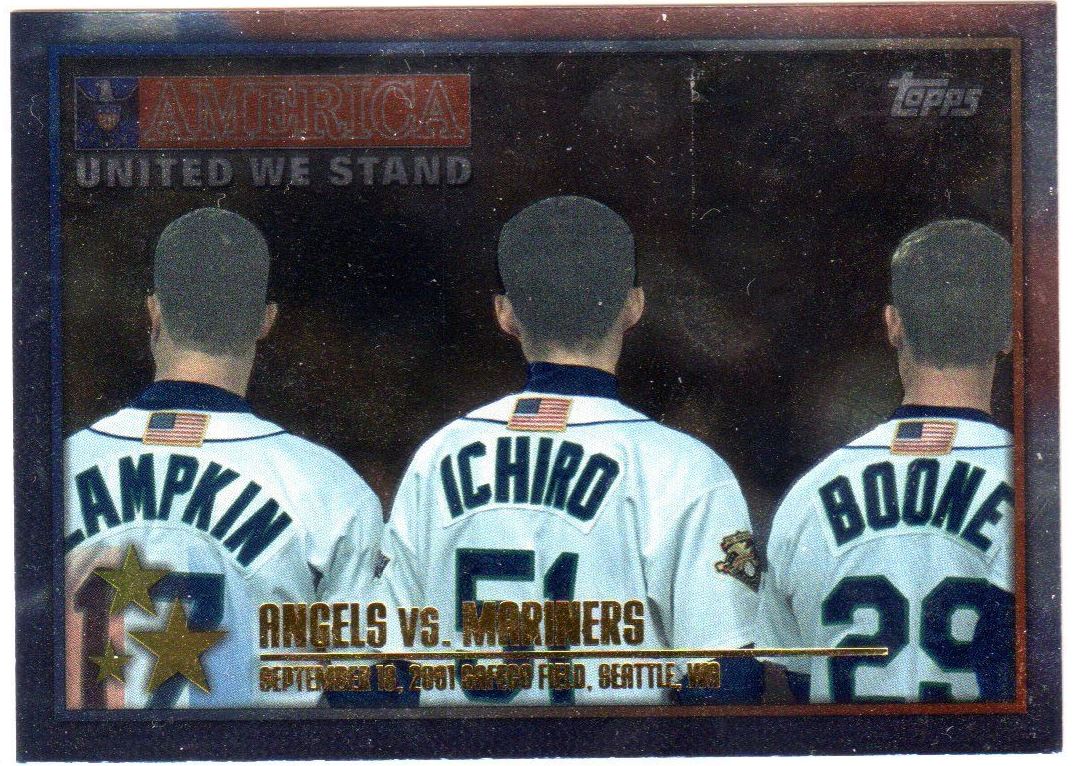

Onto number (4), which suggests that baseball cards should be printed on paper, cardboard, or a similar material. To me, this is a no-brainer. Printing plates are metal, and they’re still baseball cards. Sportflics cards from the 80s and 90s were plastic. Early tobacco issues like S74 and B18 were printed on silk and felt, respectively. 1977 Topps Cloth Stickers were — well, you get it. It would appear that material has no bearing on whether or not something is a baseball card.

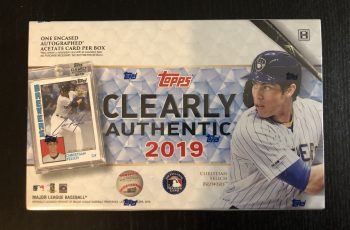

Attribute (5) suggests baseball cards have to be distributed in packs. Not so! Topps Now and Topps On Demand are single cards and sets sold online and mailed individually. Some cards, like the popular Topps Rookie Variations, come only in factory issued box sets. Strip cards from the early 1900s were only available from the counter clerk when purchasing gum or candy from the store; Exhibits cards were only available in vending machines. So although packs are the most common method of distribution, it certainly isn’t necessary.

Next, let’s go back and consider attribute (2), which states that baseball cards contain an image of a baseball player on the front. It’s easy to discard the wording “image of a baseball player.” Certainly, cards containing team photos, managers, stadiums, and even mascots are still baseball cards.

But even if we changed “image of a baseball player” to “image of a baseball-related figure,” I don’t think that a baseball card MUST have an image on the front at all. Though I readily admit that this position may not be a popular one, there is precedent for it. Cards with cut autographs, particularly from companies like Leaf, often have nothing but the autograph and a simple design or a few words on the front of the card. There are also issues like 2000 Just Mystery Autographs, which had a large question mark and silhouette on the front. Ever-popular booklet cards sometimes have nothing but the product logo on the front, with player photos on the interior (which is a dimension of cards we haven’t even discussed!). Then there’s the Schrödinger’s Cat of baseball cards, the 1990s issues of Topps Mystery Finest which came with a black adhesive layer over the front of the card; sure, if you peel it off, there’s a baseball player under there, but if you leave it on, isn’t that black later technically the front of the card? Therefore, rather than an image of something baseball-related, the item just has to have baseball-related content in order to be a baseball card.

Attribute (6) is the most important one and, to me, the only one that holds water — that the item was created with the intention of being collected. Nothing that gets classified as a baseball card doesn’t fall into this category. The item may have had other purposes, sure: for example, 1954 NY Journal American cards were used as raffle tickets of a sort. But the creators intended for people to keep them, or they wouldn’t have made them so elaborate with photos of players on them. The intent to collect them was purposeful, so that people would buy more newspapers to obtain more of them.

So, now we have a new definition of a baseball card: anything with baseball-related content that was created with the intent of being collected. You can apply this rule, and the logical steps followed above, to anything to determine if it’s a baseball card.

Take, for example, one of the bigger controversies when I’ve discussed this with people: 1964 Topps Coins. Why on earth would these not be considered baseball cards? If we determined in attribute (4) that material doesn’t matter, and we discovered in attribute (1) that size and shape don’t matter, than certainly a coin, which goes far beyond our bare-bones new definition of a baseball card, qualifies for classification.

Another question I have been asked is whether game tickets are cards. My answer is a pretty emphatic no. While the rectangular appearance and use of paper material is deceiving, tickets were created to be used for entry, not collected. Today, physical tickets barely exist anymore, and most attendees enter a ballpark with digital tickets on their phone or printed from their computer.

While talking about this subject with people I was pleased that most collectors agreed with me on this subject, even without hearing my rationale. I think for most collectors, it’s a gut instinct that if you can collect it, it’s a baseball card. Now that I’ve put the logical steps down, I hope I’ve convinced you, too.