Inside the Pack: When Heroes Die

Almost exactly one year ago, I wrote a blog post about how Kobe Bryant’s death had impacted the prices of his cards. The gist of the post was this: every time an athlete dies, his sports cards increase dramatically in value, and then eventually back off. I noted that while I understood the prices of autograph cards increasing – after all, he couldn’t sign any more cards – the trend of rookies and other base cards made no sense to me. I wrote, “there’s clearly an aspect of this for collectors that I’m missing, and I’d like to know what that is.”

I get it now.

This past Friday, Hank Aaron passed away at the age of 86. I have no real ties to The Hammer. I never saw him play as he’d been retired for a decade by the time I was even born. No one in my family was ever a Braves fan, nor did we have any ties to Atlanta. But as a young baseball fan and card collector, Aaron captivated me. The numbers 715 and 755 was one that every baseball fan knew, even if no one could tell you what Pete Rose’s career batting average was or how many strikeouts Nolan Ryan had or how many career wins Tom Seaver had.

My first Aaron card was his second-to-last, a beat-up 1975 Topps card I got at a flea market as a kid. I can remember staring at the back and marveling at the HR column. It was truly incredible to see someone be so consistent for so long. Players had down years. Players got injured. Players started their careers late, and some ended them early. Not Hank. That HR column was incredible. I knew a lot of numbers back then besides 715 and 755 – 58 home runs for Hank Greenberg, 60 for Babe Ruth, 61 for Roger Maris, 66 for Sammy Sosa, 70 for Mark McGwire. I knew Cecil Fielder had hit 50 home runs in a season. Hank Aaron? Never. Not once. I would add the numbers in my head to make sure they really added up to over 700 home runs. It didn’t make sense to me – how could he have so many home runs if he never even hit 50? Consistency – that’s how. So many of those home run numbers for over two decades were in the 30s and 40s. Year in and year out, he hit home runs. I’d do more mental math: if he hit 30 a year for 20 years, that’s 600; 40 a year for 20 years is 800; okay, I guess he really did hit that many homers!

My first Aaron card was his second-to-last, a beat-up 1975 Topps card I got at a flea market as a kid. I can remember staring at the back and marveling at the HR column. It was truly incredible to see someone be so consistent for so long. Players had down years. Players got injured. Players started their careers late, and some ended them early. Not Hank. That HR column was incredible. I knew a lot of numbers back then besides 715 and 755 – 58 home runs for Hank Greenberg, 60 for Babe Ruth, 61 for Roger Maris, 66 for Sammy Sosa, 70 for Mark McGwire. I knew Cecil Fielder had hit 50 home runs in a season. Hank Aaron? Never. Not once. I would add the numbers in my head to make sure they really added up to over 700 home runs. It didn’t make sense to me – how could he have so many home runs if he never even hit 50? Consistency – that’s how. So many of those home run numbers for over two decades were in the 30s and 40s. Year in and year out, he hit home runs. I’d do more mental math: if he hit 30 a year for 20 years, that’s 600; 40 a year for 20 years is 800; okay, I guess he really did hit that many homers!

One of my favorite pieces of trivia about Hank Aaron has always been that if you take away all the home runs he ever hit, he’d still have over 3,000 hits. That wasn’t evident from my beat-up 1975 card, on which he had 3,600 career hits to 733 home runs, but I remember hearing that once as a kid and never letting go of that fact. I also always loved the beauty of Aaron owning two-thirds of a lifetime Triple Crown when he retired. It’s hard enough to have two-thirds of a Triple Crown in a single season. For a career? That’s absurd. And no one – no one – will ever beat his record of 6,856 total bases, where he’s more than 700 bases in front of the second place finisher, Stan Musial. I always liked a person with an unbeatable record.

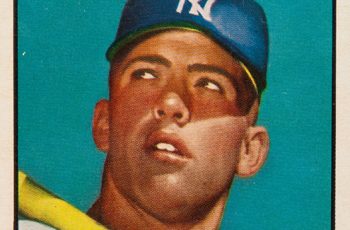

When I heard about Aaron’s passing, I went to my card show boxes, which have sat idle for a year since the start of the pandemic, and pulled out my Aarons. I have multiples of some cards. A few are beat up. I laid them all out and looked and them, and took the photo you see up top. I liked the way it looked. And even though these cards are selling for double or triple the price I had marked on them, I peeled the price stickers off and put the cards in my personal collection box instead. Do I need five 1958 Topps Aarons? I do not. I’m not even certain I need one in my collection. But for right now, I liked the walk down memory lane, thinking about the feelings I had as a kid while studying Hank Aaron cards and never dreaming I’d ever own any card beyond my creased ’75 card. If I had all these feelings about a player I never even saw play, then surely I could understand why base cards and rookies of stars like Kobe Bryant shoot up in value after they pass. When your hero dies, you want something of theirs to remember them by.