Inside the Pack: Topps #1 Card Reserved for Best Players…Usually

Topps has long used card numbers in its flagship product to highlight the best players on key cards. In general, card numbers in multiples of 50 were reserved for the biggest stars of the game, but no number has been more prestigious than #1. Since 1952, the card number has been used 9 times for league leaders, 3 teams for the World Series champions, once for a league president, once for the Commissioner, and once for the all-time home run leaders: Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron, and Willie Mays. Every other time, the card has been reserved for individual players. The list of players honored with card #1 is a virtual who’s who of titans of the sport. Leading the pack with 5 solo appearances is Alex Rodriguez; Hank Aaron and Nolan Ryan each had 3 appearances in a row! Ted Williams was not just the first player to appear twice (1954, 1957), but was also the first player to appear three times AND the first to appear back-to-back when he was given card #1 in 1958.

But over the years, there were bound to be some choices that are baffling. I thought about this as I was sorting through some old sets and came across a particularly odd inclusion in 2007 Topps (spoiler alert: it’s on the list below).

I can certainly see players being given card #1 based on a particularly strong season, even if their career didn’t pan out in hindsight. This is the case in years like 1961, when Dick Groat was given the honor following his 1960 NL MVP season. Although Groat had a great career, his MVP year looks lackluster in the context of today’s statistical understandings, but no one can fault Topps for awarding the first card in a set to the reigning MVP. Similarly, while Vince Coleman’s career fizzled the second he landed with the Mets as a free agent, his 1987 season saw him steal over 100 bases for the third year in a row — again, an achievement that makes Topps’s bestowing of card #1 totally understandable.

To determine the “worst” selections for card #1, I used the very subjective eye test. I didn’t want to use a statistic like Wins Above Replacement, because I truly don’t think it tells the whole story of how or why a player ended up on the first card in the set. (Coleman, above, is a great example — WAR has him as a worse player than teammate Terry Pendleton in 1987, but understanding how important and exciting stolen bases were in the 1980s allows us to see why Coleman made sense on card #1.) Context also allows us to understand Pete Rose’s inclusion in 1986 (he broke Ty Cobb’s hit record in 1985), Robin Yount’s presence in 1993 (he got his 3000th hit in 1992, and 1993 was to be his last year as a player), and Cal Ripken, Jr.’s appearance in 2001 (his final season).

Removing those special circumstances and using the eye test, I arrived at the five most confusing card #1 choices in Topps history, presented here in chronological order.

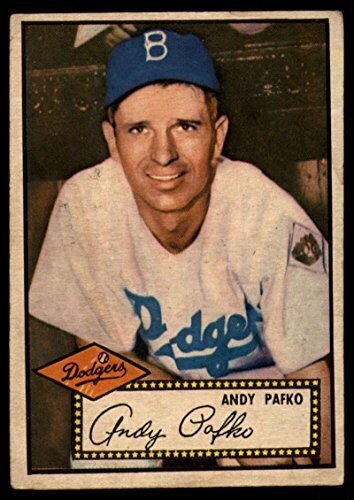

Andy Pafko (1952)

Pafko had a nice MLB career, making All Star games in 4 straight seasons from 1947 to 1950. That said, he is certainly not deserving of the most iconic card #1 of all. In 1951, not only did Pafko’s run of All Star seasons end, but he was traded from the Cubs to the Brooklyn Dodgers. Though the power hitter continued mashing home runs in New York, his batting average dipped to .249 in Brooklyn — well below his .294 career mark at that time. Still, he was honored with the first #1 on a modern baseball card.

Better choice: So many. My assumption is the desire here was for a New York-based team. A pair of catchers, Yankee Yogi Berra and Pafko’s Dodger teammate Roy Campanella, each won the 1951 MVP award and would have sufficed here.

Tony Armas (1983)

Armas was a home run masher and huge run producer for the Athletics and Red Sox in the late 70s and early 80s. But 1982 was far from his best season — in fact, it was the worst full season of his career to that point, a low point he’d only surpass with his actual 1983 season. He hit just .233 with a .275 OBP while hitting 28 home runs in 1982. His inclusion as card #1 in the 1983 set came on his fielding strength, however; the card is a Record Breakers card recognizing the 11 putouts in right field that Armas recorded in 1982.

Better choice: Rickey Henderson’s Record Breakers card is #2 in the set. Rickey was coming off his second 100-steal season, his second All Star appearance, and was young and exciting. This is a no-brainer.

Carlton Fisk (1985)

Fisk was well on his way to enshrinement in Cooperstown with by 1985, and still had a few more All Star appearances in him. But 1984 was not his year. The catching great hit just .231 with an abysmal .289 on base percentage, which represented a 51 and 65 point drops, respectively, over his career stats to that point. So how did he get here? Fisk caught all 25 innings of a very long game — a record for a catcher. The fact that he started just 81 games at catcher in 1984 was less important.

Better choice: While the 10-card Record Breakers subset contained 6 future Hall of Famers, none of them had 1984 seasons that make this a slam dunk choice. Dwight Gooden (card #3) finished second in the NL Cy Young voting, but giving a rookie card #1 would have been a gutsy call. The better choice would have been Bruce Sutter (card #9), who not only finished 3rd in the NL Cy Young voting, but also finished 6th in NL MVP voting after a 45 save season with a 1.54 ERA.

George Bell (1989)

George Bell was a huge star in the 80s, posting many big seasons, including a 1987 MVP campaign. 1988 would have been a perfect time to award him card #1, but after giving that honor to Vince Coleman, Topps seems to have rewarded Bell after the fact — undeservingly so — with card #1 in 1989. Bell’s 1988 season was a huge disappointment, especially seen in the light of his 1987 season. His .269/.304/.446 slash line represented a 206 point drop in OPS from his 1987 season, and 1988 was the first season in 5 years he didn’t receive an MVP vote, but he did hit 3 home runs on Opening Day, which was apparently enough to erase the next 161 games from everyone’s mind.

Better choice: This was yet another Record Breaker subset card, but so was Orel Hershiser, who was relegated to card #5 after throwing a record 59 scoreless innings in a row and winning the 1988 NL Cy Young unanimously. His scoreless innings record still stands today! Card #5 — really???

John Lackey (2007)

Lackey was a solid if unspectacular pitcher over his 15 year career, but his inclusion as card #1 is particularly curious given that it came in 2007. Lackey burst onto the scene with the Angels in 2002, starting Game 7 of the World Series as a rookie, and becoming just the 2nd rookie ever to start and win a World Series Game 7. So perhaps a 2003 card #1 wouldn’t have been crazy, but 2007? That one is difficult to figure out. The year prior, Lackey went 12-11 with a 3.56 ERA and 1.26 WHIP. He wasn’t an All Star, nor did he receive a single Cy Young vote. How he ended up with card #1 is beyond me, but it ended up being a fairly prescient choice: 2007 became Lackey’s only All-Star season, and he finished 3rd in the Cy Young voting that year.

Better choice: You could go in any number of directions here because this choice is so odd. Lackey wasn’t even the best pitcher on his team — that claim belongs to Jered Weaver, who debuted in 2006, played just 19 games, but went 11-2 with a 2.56 ERA and 1.03 WHIP. If for some reason they wanted to go with an Angels pitcher, they could have placed Weaver on card #1, I guess.